Strategy lessons:

Determine importance

Separating out what is important from what is not and combining the new information with background knowledge is the definition of comprehension. Readers determine what is most important at the word level first. Readers determine what is important from what is not at the whole-text level. Students collect the most important information from the pages in order to comprehend main ideas and themes of texts. Students discuss nonfiction during this unit because what is most important is less ambiguous than in fiction.

Learning targets

- I can read nonfiction texts using the concepts of print to help me.

- I can prioritize what’s most important at the word level and at the whole text level.

- I can prepare to talk about what’s most important with a small group of readers.

- I can defend my theories of what is important with my peers and to my teacher.

- I can talk in a conference with my teacher about my reading progress.

- I can determine the main idea.

- I can read a text and determine what is important to remember.

Getting started: What's important?

Determining what is most important is critical to building life-long success. Think of buying a house or car, choosing a career, investing in stocks, making financial decisions, etc. All these tasks require separating important from unimportant information. So, learning this strategy is directly linked to success.

From scientists we know that we start by teaching readers to distinguish what's important at the word level. For example, in the riddle, "I sleep by day and I fly by night. I have no feathers to aid my flight," the words your eyes will spend a millisecond longer on are sleep, day, fly, night and feathers. These words are called contentives. The other words in my riddle are functors. Their function is to hold the sentence together. To understand what is important at the whole-text level, students must learn to identify what is important at the word level. (Mosaic of Thought, 2007) (The answer to my riddle is a bat, by the way.)

However, teaching what is important is not easy and learning to separate what's important from what's not is difficult, too. If you’ve ever handed a learner a highlighter to underline what is important, you know that the page comes back completely colored. “It’s all important!” students explain. Keene found adult learners to be similar. When adults discussed texts, all defended their beliefs. In other words, it was hard for adults to agree on what was most important as well.

We are not alone

Ellin Keene, author of Mosaic of Thought, explains that our students are not alone. "Determining what is important - arguing and defending - helps build reasoning skills. Most students are competent readers. They pronounce words correctly, miss few words and sound out words they didn't know." Keene explains her research. "But many were so disconnected from the text, especially expository text, that they were often unaware of what they were reading..."

Unfortunately, Keene's words speak directly to me and my experience. Sometimes, when my students see an unfamiliar word, they call a nonsense word and keep going. Usually, the only connection between the word they said and the word on the page is the same first letter. Some have so little sense of story structure that they stop reading at the end of the page, even when they're not at the end of the story. "They were often unaware of what they were reading," definitely applies to the readers I see. Obviously, these students need reading help. I had to figure out how to teach students to read for meaning.

Reading conferences

I guarantee you the best way to start teaching determining importance is by re-arranging your schedule like I did. The most important teaching is in a one-on-one setting. Get to know your students by listening to them read no matter whether they are in elementary, middle or high school. It doesn’t have to be long - 5 minutes - I promise! In middle and high school, I conferred just a few times in a semester, but it was the one thing students mentioned as helping them on their end-of-the-year survey.

Praise what readers do well. Teach one thing. Keep a record of what you say. Even in a mini conference, you can show a student how to say the right word, read to the end of the story, and "defend, rethink, question and draw conclusions," as noted in Keene’s words above. Over time, the mini conferences add up and you’ve modeled many techniques personally. Then, ask the students to keep a goal sheet. Students know their personal reading goal. Set aside time for students to reflect on that goal and if they have mastered it, set a new goal. Teach to their goals in your small-group time, mini lessons and 1-1 conference time.

Minilessons

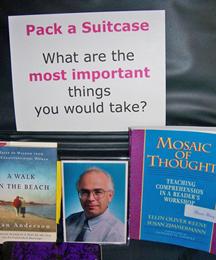

To support your conferences, you need minilessons. I like to introduce determining importance by asking students to fill a suitcase with 10 of their most important items - or 5 items in the primary grades. (See photo.) They draw pictures or cut pictures out of magazines. When forced with choosing the most important items in their lives, they begin to grasp the process their brains work through in order to prioritize. I can build on this concrete exercise when talking about main ideas in reading and writing.

To support your conferences, you need minilessons. I like to introduce determining importance by asking students to fill a suitcase with 10 of their most important items - or 5 items in the primary grades. (See photo.) They draw pictures or cut pictures out of magazines. When forced with choosing the most important items in their lives, they begin to grasp the process their brains work through in order to prioritize. I can build on this concrete exercise when talking about main ideas in reading and writing.

Retelling

Another place to start is by retelling. Whether the students retell orally or in writing, they are forced to choose the important details to tell. Plenty of practice will improve their writing and reading skills. I also like that tutors, volunteers and parents can listen to readers retell stories and ask questions so students become aware of important, missing details.

A retelling station is a very easy center to keep up all year. All you need is a basket of books, which the teacher updates occasionally, and an assessment sheet. Partners go there to read together and retell the stories to one another.

Small Groups

Also, schedule time for conversation in small groups of 4-6 students. Just talking about selections in a more intimate environment gives students the opportunity to think out loud and consider other perspectives more thoroughly. It’s in reading groups that students "defend, rethink, question and draw their own conclusions.” I never imagined that metacognition could be unleashed with such power when given the chance to practice.

When I watch adults talk, they veer on and off course, but the work gets done. So too with kids. Even though I'm uncomfortable with exactly what is getting accomplished in these groups sometimes, I know that the talk time is important. Furthermore, that's when the seeds for writing ideas grow. And by the end of the year, the groups don't look as messy and the work not as ambiguous if they have time to practice with me as their guide.

Many of my lessons are all about breaking down how people talk to one another: how we listen, show others we listen, disagree with one another, and reach consensus, for example.

I structure these groups in such a way that students talk about main ideas, author's purpose, and themes and support their ideas with evidence. Talking, even for brief periods of time, helps students determine what's most important, comprehend their texts and tests, and prepare them for those future life skills like buying a house. In addition, I know where comprehension breaks down and can teach directly to the misunderstandings.